Greg Duncan talks about why a child allowance and an EITC are the best route to cutting child poverty in half.

Greg Duncan, economist and Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Irvine, has spent his career studying child poverty. A superstar in the field (though he’d never cop to that), he most recently chaired the National Academies committee that issued the 2019 report, “Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty,” or how to cut child poverty in half.

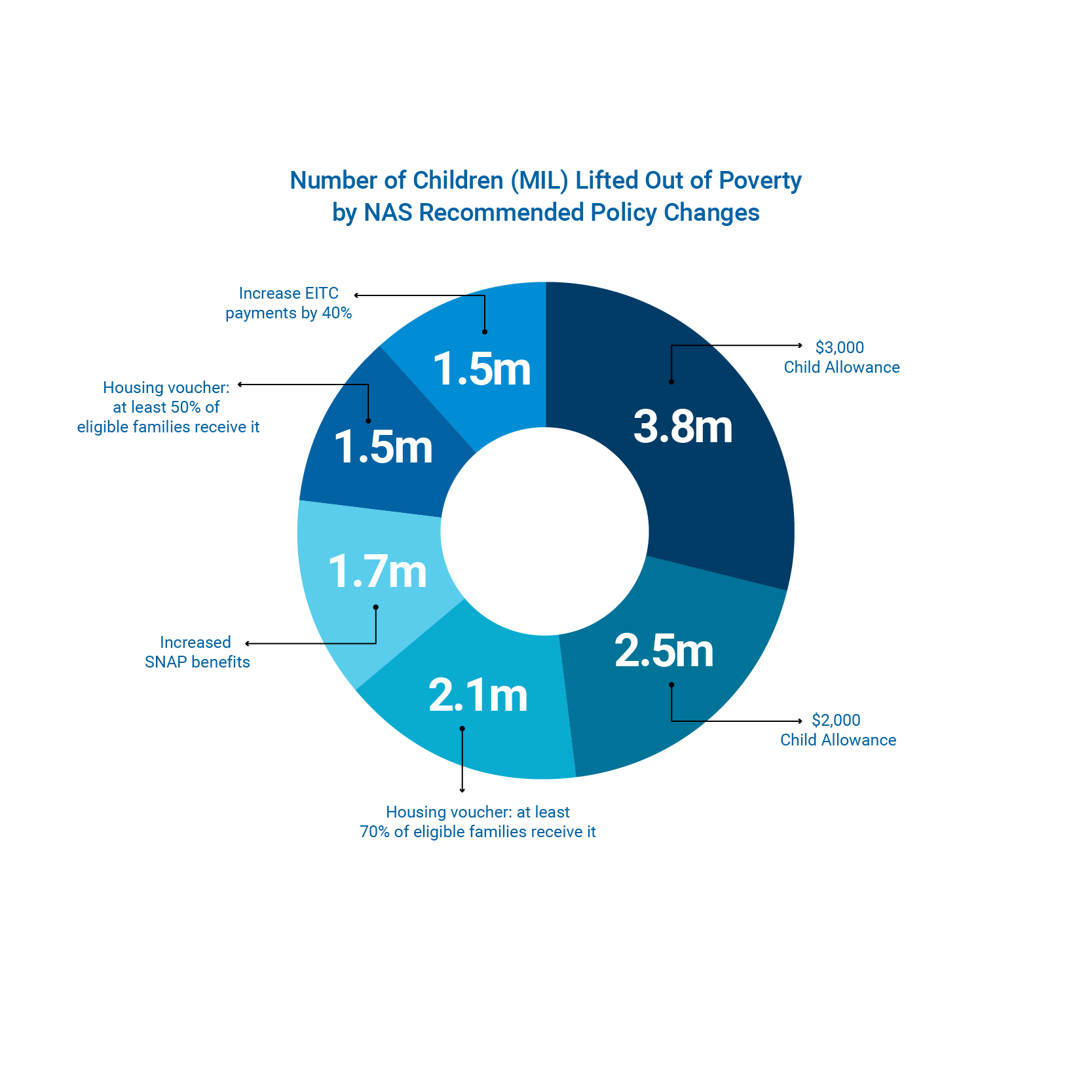

A key finding of the NAS report is that an expanded child allowance—similar to the Family Health Project’s approach—comes closest to meeting the goal of cutting poverty in half. A child allowance is a monthly stipend to families with children. Seventeen advanced nations offer one.

But even better, Duncan thinks, is to combine a child allowance with a modest expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a tax rebate that essentially boosts many low-income workers’ wages by 40 percent. The two programs combined would lift millions of children out of poverty, increase work and offer a cushion when recessions or other family disasters strike.

FHP: It must feel gratifying that policymakers are listening to the research. President Biden and Sen. Mitt Romney have both released plans that feature a child allowance along with other recommendations in the report. How closely do their plans mirror the NAS recommendations?

Greg Duncan: Romney’s plan would provide a generous monthly child allowance but cut the EITC to fund it, which is not a good idea. Without an EITC it also has no work incentives, which is surprising for a Republican plan. It does have a pro-family angle, however. Romney’s plan provides some cover for Biden to say there’s bipartisan support.

Biden’s plan is nearly as generous but doesn’t cut the EITC or other safety net programs. [The plan increases the current Child Tax Credit to at least $3,000 a year and extends it to all families, even those earning too little to file taxes, and makes it monthly instead of annually. The NAS report estimates such a program would cost $54 billion and lift 4 million children out of poverty.]

The child allowance is a game-changer for potentially improving the quality of the home environment for kids and providing a measure of economic stability to the family.

With the monthly child allowance, the idea is that you’re letting parents make decisions about what spending most benefits their children. That the payment is monthly instead of annually is the most exciting development. It’s a game-changer for potentially improving the quality of the home environment for kids and providing a measure of economic stability to the family.

FHP: I should be clear that the NAS report shows that a package approach is the best way to cut child poverty and increase work.

Greg Duncan: In our report, nothing worked better than a child allowance at cutting child poverty. It didn’t eliminate child poverty, but it was the relatively best performer. The real insight is that if you combine a $2,000 child allowance with a modest expansion of the EITC and reform the child care tax credit, you can reduce child poverty by more than a third and increase employment and earnings substantially. This package would cost about $44 billion per year.

In our report, nothing worked better than a child allowance at cutting child poverty.

FHP: The NAS report finds that work-based policies alone, like an expanded EITC or a higher the minimum wage, would not cut child poverty in half. Does that mean that work doesn’t fix the problem?

Greg Duncan: A package of work-based programs alone only would cost less than $10 billion per year but would reduce child poverty by only 18 percent. They also have little effect on deep poverty [defined as living on less than half the poverty threshold, or about $11,000 for a family of three in 2020].

“Work-based programs alone only reduce poverty by 18 percent.”

Greg Duncan: But let’s be clear: employment lifts a lot of children out of poverty. Work-based programs are an absolutely essential part of the safety net. On balance you don’t want to discourage work. But work-based incomes go up and down with economic conditions and there are still a significant number of kids in families where no one is working or working very little, so you don’t make much headway on child poverty.

FHP: Why do we focus on work and changing behavior in our poverty policies?

Greg Duncan: Because we’re America! Seriously. Americans are not ungenerous, but they really like programs that are structured to help people help themselves. We don’t like to address the deeper structural issues behind poverty and inequality.

FHP: Is there a role for the private sector in reducing child poverty? Child poverty certainly costs the nation an enormous amount–estimates of up to $1 trillion or 5 percent of GDP—so it would be in the private sector’s interest to abolish it.

Greg Duncan: There’s an important role for the private sector to develop scalable solutions. And I would argue to evaluate them in a way that shows costs and benefits unambiguously. But funding the programs is another issue. If you want a really broad scale, thinking that it can be privately financed and run, I’m not convinced. The government can send checks out efficiently_just look at Social Security—and it has deep pockets. What the private sector can do, however, is demonstrate that cash payments have a beneficial effect and that we really should be thinking about it in the national debate.

The weight of evidence would suggest that money does matter for kids’ well-being.

FHP: The Family Health Program is focused on creating a child cash allowance model that can go to scale, which many public health programs have trouble doing. They might be highly effective, but they’re expensive and often short-term. Thoughts?

Greg Duncan: Fresh thinking is always welcome. In theory, I think the Family Health Plan could indeed scale. It’s got all the elements. I’m sure that without the bureaucracy and due process worries it can be done very efficiently. And then you can take the lessons learned and inform other efforts.

FHP: Bottom line? Will more money each month have an impact on children’s lives?

Greg Duncan: While there’s still a few questions about the impact of more money, the weight of evidence would suggest that money does matter for kids’ well-being.